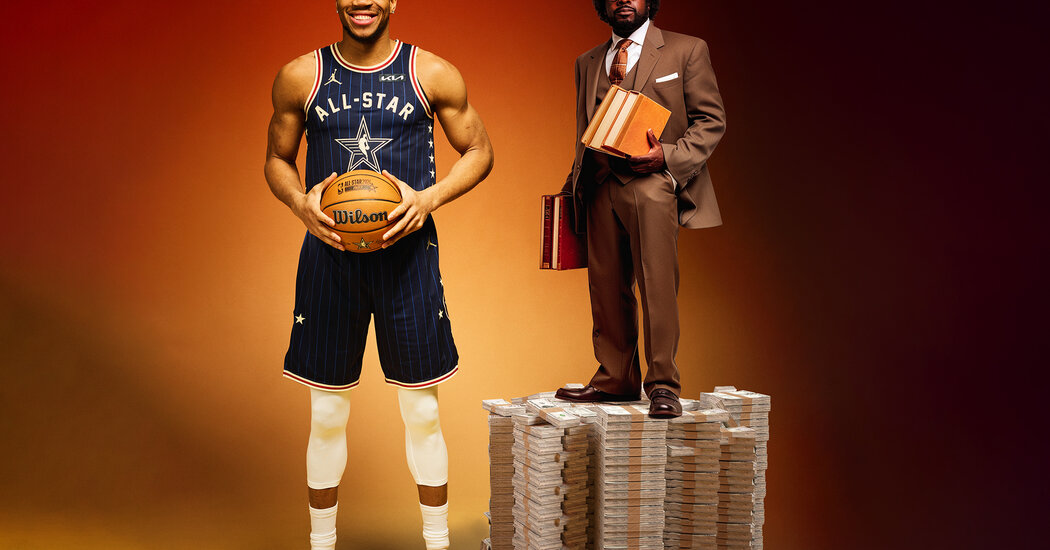

Pay for Lawyers Is So High People Are Comparing It to the N.B.A.

Hotshot Wall Street lawyers are now so in demand that bidding wars between firms for their services can resemble the frenzy among teams to sign star athletes.

Eight-figure pay packages — rare a decade ago — are increasingly common for corporate lawyers at the top of their game, and many of these new heavy hitters have one thing in common: private equity.

In recent years, highly profitable private equity giants like Apollo, Blackstone and KKR have moved beyond company buyouts into real estate, private lending, insurance and other businesses, amassing trillions of dollars in assets. As their demand for legal services has skyrocketed, they have become big revenue drivers for law firms.

This is pushing up lawyers’ pay across the industry, including at some of Wall Street’s most prestigious firms, such as Kirkland & Ellis; Simpson Thacher & Bartlett; Davis Polk; Latham & Watkins; and Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Lawyers with close ties to private equity increasingly enjoy pay and prestige similar to those of star lawyers who represent America’s blue-chip companies and advise them on high-profile mergers, takeover battles and litigation.

Numerous people compared it to a star-centric system like the N.B.A., but others worried that higher and higher pay had gotten out of hand and could strain the law firms forced to stretch their budgets to keep talent from leaving.

“Twenty million dollars is the new $10 million,” said Sabina Lippman, a partner and co-founder of the legal recruiter Lippman Jungers. In the past few years, at least 10 law firms have spent — or acknowledged to Ms. Lippman that they need to spend — around $20 million a year or more to lure the highest-profile lawyers.

One hiring partner at a law firm said $20 million pay packages were usually reserved for those who could bring in more than $100 million in annual revenue for a firm.

Last year, six partners at Kirkland, including some who were recruited during the year, each made at least $25 million, according to people with knowledge of the arrangements who weren’t authorized to discuss pay publicly. Several others in its London office made around $20 million.

One partner at a law firm said pay for top lawyers had roughly tripled in the past five years.

The take-home pay of some top lawyers is now approaching that of big bank chiefs. Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank, made roughly $36 million last year. David Solomon of Goldman Sachs earned about $31 million over the same period.

At the center of the action is Kirkland, a 115-year-old law firm founded in Chicago that made an early play for private equity clients when few rivals saw them as big moneymakers. About a decade ago, Kirkland began poaching heavy hitters at rival law firms — many based in New York — who had longstanding relationships with the biggest private equity players.

That inspired fierce competition among top law firms, including Simpson, Latham, Davis Polk and Paul, Weiss. Some have changed their compensation structures or stretched their budgets to keep stars from leaving. Others have countered by raiding Kirkland to build their own private equity businesses.

“Firms do not feel like they can only think about being defensive with respect to their talent,” said Scott Yaccarino, co-founder of the legal recruiting firm Empire Search Partners. “They have to be on the offense, too.”

Lawyers have earned multimillion-dollar pay packages for more than a decade. When Scott A. Barshay, one of the industry’s pre-eminent mergers-and-acquisitions lawyers, left Cravath, Swaine & Moore to join Paul, Weiss in 2016, his pay package of $9.5 million created a stir in the industry. (Mr. Barshay’s compensation has risen significantly since then, two people with knowledge of the contract said.)

But the recent jump in pay has happened at a dizzying pace and for many more lawyers. Coupled with the fierce poaching, it is swiftly reshaping the economics of major law firms. Kirkland has even guaranteed some hires fixed shares in the partnership for several years, according to several people with knowledge of the contracts. In some instances, it has extended forgivable loans as sweeteners.

Last year, Kirkland hired away Alvaro Membrillera, a noted private equity lawyer in London who counts KKR as a key client, from Paul, Weiss for around $14 million and a multiyear guarantee, according to two people with knowledge of the contract.

White & Case recently hired O. Keith Hallam III, a partner from Cravath with private equity clients, for roughly $14 million a year, according to a person with knowledge of the contract. The firm also hired Taurie M. Zeitzer, a private equity lawyer at Paul, Weiss, for around the same amount, another person with knowledge of the contract said.

To some, the changing landscape represents a more meritocratic system in which partners can expect pay based on talent rather than seniority. Cravath, a storied, 205-year-old firm, long followed the so-called lock-step system linked to seniority, but modified it in 2021. Debevoise & Plimpton is one of the few remaining firms that continue to follow the lock-step model.

“Law firms have gotten a lot more commercial in how they run themselves,” said Neil Barr, the chair and managing partner of Davis Polk. “Firms are operating like businesses rather than old-school partnerships, and it’s led to more rational business behavior.”

Kirkland’s early bet on private equity has paid off handsomely. Globally, private equity firms managed $8.7 trillion in assets in 2023 — more than five times what they oversaw at the onset of the financial crisis in 2007, according to the data provider Preqin. Blackstone alone manages more than $1 trillion in assets, and other firms, including Apollo, Ares, KKR and Brookfield, collectively oversee trillions more.

As the private equity business took off, Kirkland’s clients began directing hundreds of millions of dollars in business its way each year. In 2023, Kirkland made more than $7 billion in gross revenue, according to The American Lawyer’s annual ranking, making it the highest-grossing law firm in the world.

A single firm like Blackstone or KKR can generate legal work from the constellation of companies, banks and others in its universe. For instance, even though Blackstone’s main law firm is Simpson, it paid Kirkland — one of its secondary law firms — $41.6 million in 2023, according to a regulatory filing.

“The private equity clients of these firms — they mint money,” said Mark Rosen, the chief executive and chairman of the legal recruiting firm Mark Bruce International.

Simpson, an illustrious Wall Street firm with roots in the Gilded Age and one of the largest private equity practices, has been a particular target of poaching by Kirkland. One person with knowledge of the rivalry called the firm Kirkland’s “farm team.” Kate Slaasted, a spokeswoman for Kirkland, said in an email: “As a firm, we have the highest regard for Simpson Thacher.”

At least seven top partners from Simpson, including Andrew Calder and Peter Martelli, have jumped to Kirkland in the past decade. Kirkland also poached Jennifer S. Perkins, a star lawyer from Latham who has represented KKR on some of its deals, to join its private equity practice.

Mr. Calder and Jon A. Ballis, the chairman of Kirkland, were among the partners who made at least $25 million last year, according to three people with knowledge of the compensation details. Mr. Calder and Melissa D. Kalka, also a partner at Kirkland, work closely with Global Infrastructure Partners, the private equity firm that recently announced a deal to sell itself to BlackRock for $12.5 billion.

In 2023, Paul, Weiss — which counts Apollo Global Management among its top clients and is aggressively building its private equity business — poached several Kirkland lawyers to build out its London office. The firm also hired Eric J. Wedel, whose clients include Bain Capital, KKR and Warburg Pincus, away from Kirkland, and Jim Langston, another private equity-focused lawyer, from Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton.

Simpson has altered its pay structure in the past year so that it can be more competitive with Kirkland and other rivals. “We intentionally made the decision to adjust our compensation structure to attract and retain the best talent in strategically important practices across our global platform,” Alden Millard, chair of Simpson’s executive committee, wrote in an email.

One sign of the frenzied nature of hiring: the use of multiyear compensation guarantees to attract lawyers. These fell out of favor after Dewey & LeBoeuf filed for bankruptcy in 2012, unable to meet millions of dollars in fixed payments and bonuses it had promised partners. Now, a different type of guaranteed payment has become popular.

Some firms are awarding new hires a number of shares in the partnership for a set period, typically in the range of two to five years. Such offers are attractive because they ensure a specific share of a firm’s profits irrespective of its annual performance.

This frenzy has meant that even lawyers without private equity connections have seen their pay rise. Freshfields — a big British firm that is building a beachhead in the United States — has recruited lawyers in the range of $10 million to $15 million, and provided additional pay guarantees to some, according to three people with direct knowledge of the compensation details.

“Law firms want people who are going to be motivated based on culture,” said Ms. Lippman, the recruiter. “But at some point if you have this big difference between firms, everyone has a price.”